Dear Readers,

I stopped posting abruptly in July. The story was told, and, fortunately, there is no sequel. I was happy to know that the people I most wanted to reach, including my son, certain of my grandchildren and their families and so many of my friends and relatives at the time of the fateful, mostly hateful happenings in this particular narrative had found my posts. I heard from many people, even though there are few “likes” on the writings. I think “like” is probably a hard button to push for much of this stuff but am nevertheless grateful to everyone who did push a like or send me a message. The connection is so helpful. Some of you, who were learning about certain matters for the first time about some of your closest relatives helped just by subscribing, so that I knew that you were, indeed, reading.

Thank you for being there.

Looking back, there are many literary references in the series about which some may enjoy reflection.

Of course, my entire publication was as a result of my son publishing Part I of his memoirs and announcing publicly for the first time that he was adopted. Back in December, 2022, I was horrified to read of the upcoming publication. It brought back nasty memories of everything about any interaction I had ever had with him and his keeper, his wife. But since he did decide to come out publicly, I dug up all of the texts I had written between 2000 and 2018 about the horrible time of his conception and birth and the equally horrible time knowing my son and his wife and put it all together. This Blog was not only to put up a mirror to him and his wife of how someone experienced them during the period immediately before and after their marriage. It was also to warn them before they published Part II, which I assumed would cover the unfortunate time in which I knew them.1

My son’s memoir also has many literary references, including much praise of Thomas Mann, mostly in the context of the latter being a bi-sexual family man – like my son, I thought, while reading his musings. His fondness for Thomas Mann was one of the things he and I found out we had in common. Both of us were Thomas Mann afficionados in our estranged, strange youths. Mann’s oeuvre is not the everyday choice of 17-20-year-olds but my son and I both had a strange attraction to his literature. We read the short stories and novels like The Magic Mountain or Dr. Faustus, in translation of course, while otherwise living the life of a crazy teenager.

I was thinking about this when I realized, after getting some warning subscriptions to my posts from estranged relatives which let me know they were watching, that Mann also got lots of grief after publishing his first novel, Buddenbrooks, which describes the decline of a bourgeois family in northern Germany (Lübeck, his family) beginning in 1835. Even though Mann was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1929, mostly for Buddenbrooks, he was shunned after its publication by friends, relations and townsfolk in Lübeck who were directly identifiable in the prose and not entirely positively portrayed.

In Mann’s first novel, just as in my posts, the female characters take all the hard falls in order to prop up the patriarchy, which, in the case of his family just as in mine, was failing to take care of anyone while treading the path of convention and keeping up appearances. Fortunately, my family is not as invested in a family business as the Buddenbrooks were.

Of course, Mann never indicated that he sympathised with any feminine cause or even recognised the unfairness at hand. He was just a young lad, (26 at publication) telling his story from matters observed first-hand. In fact, judging from depictions of circe-like femininity in the The Magic Mountain, I am pretty certain that Mann ascribed more to the Wagnerian view of the feminine, as depicted in Tannhäuser. You can get lost on the Venusberg – the realm of the feminine - but then you may never come back to the rational world of Henry Higgins, and even if you did (as the hero of Tannhäuser), your fellow man will collectively despise and condemn you as irretrievably immoral for your sojourn in the collective feminine. 2

Of course Mann himself was also attracted to lovely young men, a convenient lust which avoided the Anglo-Saxon male’s cultural bias against the messy, incomprehensible, essentially un-Christian matter of female desire. Women were for procreation only, under the auspices of the Pope or some protestant Deacon’s club.

Between men and women, there was to be, essentially, spiritually, apartheid.

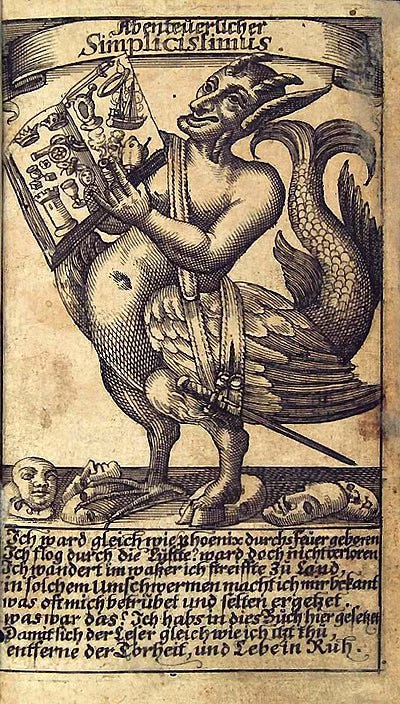

My favorite Thomas Mann novel is Felix Krull, Confessions of a Confidence Man.3 I first read this book in 1971 in a seminar on religion and literature taught by Dr. Richard Rubinstein of the Florida State University Religion department. We read about eight picaresque novels, and it was one of the greatest literature classes I ever took. Even though Dr. Rubinstein had been directly, tragically affected by the Holocaust, he introduced us to some great works of German literature — not only Felix Krull, but also Simplicissimus4 (set in the 30 Years’s War) and The Tin Drum5 (set in World War II Germany). It was not immediately obvious what the prescribed novels had to do with religion, and it turned out that they had more to do with the end of religion. Dr. Rubinstein was no longer conventionally “religious” after the Holocaust but he was a world-renowned scholar on Holocaust theology: (Rubinstein) argued that Jews (and Christians) who accept the traditional belief that God has chosen Israel and acts providentially in history must either interpret that Holocaust as divine punishment or as the most radical challenge ever to traditional belief.6

Appropriately, the heroes (or anti-heroes) of a picaresque novel are also not religious, do not follow any doctrine or dogma other than that of their own survival in a harsh world. They operate on the edge of society, not from or subject to a power center, such as the Church.

Each of these three novels is also classified as a Bildungsroman — a book about the worldly education of the hero — as my son also denotes his memoir. Fifty percent of the population of what is now Germany was decimated during the Thirty Years’ War7 (1618 - 1648), the setting of Simplicissimus, in which the hero was kidnapped by marauding soldiers at such a young age that he doesn’t even know his name. In The Tin Drum, Oskar Matzerath, who lives in Danzig (now Poland but geographically part of Eastern Pomerania, in Germany up to the end of World War II) is caught between his identity as a German, like his NAZI father, and as a Pole in the free Hanseatic city of Danzig, like his mother’s lover, who he knows could also have been his father. Felix Krull has no real identity. His entire being is an act which takes him out of the working class into which he had been involuntarily plunged after his father went bankrupt, and it is given form by his narration. In each of these tales, the hero is in a situation in which there is no going back and there is nothing to go back to.

The hero of a picaresque novel is a Hermes-like figure – neither black nor white, sometimes of uncertain sexual tendency, quick-moving, changeable. These characters are often very physically attractive (Felix Krull) and/or have a unique, often strange talent or facility (Oskar Matzerath). They usually narrate their own story, which is not always entirely reliably true. Due to their shifting nature, the reader is often drawn into the narrator’s view of what would otherwise be seen as their anti-social behaviour.

Felix Krull is born a musical prodigy but his family loses everything, he is forced out of his comfortable, bourgeois existence and must join the low, working class. Felix is a master of the surface of things — in costume with exquisite manners. He likes men and women, and he understands that we are all just playing a role. He wants to pick his, and he moves fluidly between the classes, never truly attaching himself to another person.

The Tin Drum’s Oskar Matzerath is born with fully-developed, adult mental facilities. When he turns three, he decides not to grow further after hearing his putative NAZI father announce that he will grow up to become a grocer. Oskar is also able to screech at such a high pitch that objects fall apart. He plays his tin drum incessantly (it is his protest) and, near the end of the book, is in a jazz band.

Both Felix Krull and Oskar Matzerath regularly engage in criminal, manipulative and otherwise immoral behaviour. Felix routinely steals, lies, seduces under false premises and is essentially a fraud. Among other things, Oskar is arguably responsible for the death of both of his putative fathers. At the beginning of the war and just after the German occupation of Poland, knowing the German army is there, he leads his Polish father (his mother’s lover) to the post office to pick up a new tin drum he has ordered, and the Polish father is shot and then celebrated as a Polish war hero. Later, at the end of the war, he presents his NAZI father with his NAZI badge which the latter had otherwise always proudly worn, just as the latter is being questioned by Russian soldiers, causing his father to choke to death on the badge which he is trying to hide. Before that though, Oskar takes his NAZI father’s second wife as his lover, after his mother has died, and believes he is the father of his own half-brother. All of this in the body of a three-year old.

Picaresque characters are, at some point, safely removed from the society in which they ran amok, and they usually like to make it seem that it was by their own choice: Oskar narrates his story from a mental institute, and it seems that Felix is also narrating his story from some sort of confinement. The hero of Simplicissimus returns to the life of a hermit in the woods, having had enough of the world after wandering the Holy Roman Empire during the 30 Years’ War, living by his wits and rising from rags to riches.

As I write this, I realize that my son is also a quixotic, picaresque character. Removed from his origins as a helpless infant (Simplicissimus), he is, while being raised strictly in the Patriarchy, eternally unable to even identify the man who was his father (The Tin Drum), and required to reinvent himself after undergoing deathly tribulations of the spirit as a result of not knowing who or where he came from. He believes he was descended from what he calls “Old Testament shame” — another name for Patriarchal shame (omg, could be a product of the Venusberg). Like Felix Krull, he craves high respectability which he associates primarily with worldly wealth in an economic caste system. According to my son’s book, he was admitted to various institutions on many different occasions to cure his addictions; he routinely committed drug-related crimes; he betrayed many who tried to help him when he was a drug addict and introduced friends to heroin who died soon thereafter from their addictions. His gift, his unique facility, is music, the definition of his origins. With music, he reinvented himself and saved his own life.

He is certainly Hermes-like, the trickster, the one of changeable faces; and because I have experienced the visage he never shows to the outside world, I know that his other, respectable face is not the whole truth. I also doubt that he really believes he has been saved by some Father God, as he claims in his book. All the fathers have failed him, just as have the fathers in Simplicissimus (their patriarchal wars), Felix Krull (his father is as empty a vessel as Krull but has no talent) and The Tin Drum (who is his father and why haven’t they taken care of him?) My son has never been saved by a source outside of himself, and, just like our literary picaresque heroes, he has no need of it. But he does know how to say what he thinks you will find respectable. Like Felix Krull, he always wants to give an impression of high respectability, no matter how shallow it is or irrelevant to his true self. Lack of respectability, something he believes is an innate trait, like nobility, rather than earned, is still his biggest fear, and it was the major component in the usual accusations of shame he threw my way.

Respectability or lack thereof is how he divides himself from others. So not only has he not been saved, he is also still suffering from being raised by people who told him his origin was trash. He is a male Cinderella who has been freed from his false, tortured Heimat but still cannot forget the tribulations. That wound will never heal. As a result, he poses as the most highly-mannered, gracious guy (Felix Krull did it best), and most recently, even the one with loving-kindness wisdom from a guru who was the first one to teach him, post-40 years of age, the high spiritual bar of impartiality when interacting with your fellow human beings.8 It was right there in his Bible all along of course but what impressed me the most was the fact that he had apparently never really experienced kindness until he entered the world of his music far away from the false home.9 There was truly no balm back there in West Hartford, and it was not Gilead.

In his July interview with Nate Chinen in Chicago, published in the latter’s page here on Substack, The Gig, he now says that Part II will not continue his autobiography as such but that it will be more about his Jazz canon.

After writing this, I found a statement in the forward to a biography of Thomas Mann (Hans Wysling, Yvonne Schmidlin,Thomas Mann, Ein Leben in Bildern (Fischer Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1997) p. 12: “Thomas Mann stellte sein Werk in die Nachfolge Wagners. Die Nibelungen-Tetralogie ist schon da als Hintergrundschema von “Buddenbrooks” . . . .” Thomas Mann placed his work in succession to Wagner. The Nibelungen Trilogy is already in the background schematic of The Buddenbrooks . . . .” (my translation).

Mann, Thomas, Confessions of Felix Krull, Confidence Man (Knopf 1992).

Hans Jakob Christoffel von Grimmelshausen, Simplicissimus (Dedalus 2016).

Grass, Günther, The Tin Drum (Vintage Books 2005).

Rubinstein, Richard, After Auschwitz (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2d Edition 1992), from the Preface.)

The Thirty Years’ War (1618 - 1648) was a continuation of the armed conflict throughout Europe (in this case central Europe, particularly the geographical area now known as Germany) between the forces of the protestant reformation (Sweden and Denmark in particular) and the former ruler of Europe - the Holy Roman Empire. In the German-speaking part of this theatre of war, more than 50% of the inhabitants of the geographical area of what is now Germany were slaughtered or starved to death. The war ended in the Peace of Westphalia (referring to the area in Eastern Frisia, Germany, where it was signed) in 1648 and concluded final recognition of the Dutch independence from Spain, among other things. See

Note 1, supra. He talks about this in his interview with Nate Chinen.

Id. He also makes this statement in his book.

This is Roger Salandi. You probably don't remember me. I met you at FSU after I transferred there in Fall 1970. I knew you as Jane Ellen, and we met through a mutual friendship with Mark Ridlehoover, who was my roommate at the time. Your father was one of my professors since I majored in applied mathematics. You popped up on that "people you may know" line on Facebook (how does that work anyway?). That led me to your Substack writings. I am so sorry to hear of the undeserved emotional trauma you were subjected to back then, and wish you contentment and peace.